First of all, it should be noted that nobody should share their passwords (or their underwear). What has been in doubt for some time now, however, is forcing people to change their passwords at regular intervals. In recent years, companies especially have been issuing guidelines requiring staff to change their passwords every four weeks.

None other than William Burr, the author of the original NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) recommendation from 2003, on which many of the rules still in use are based, has distanced himself from this recommendation, describing it as outdated and even harmful.

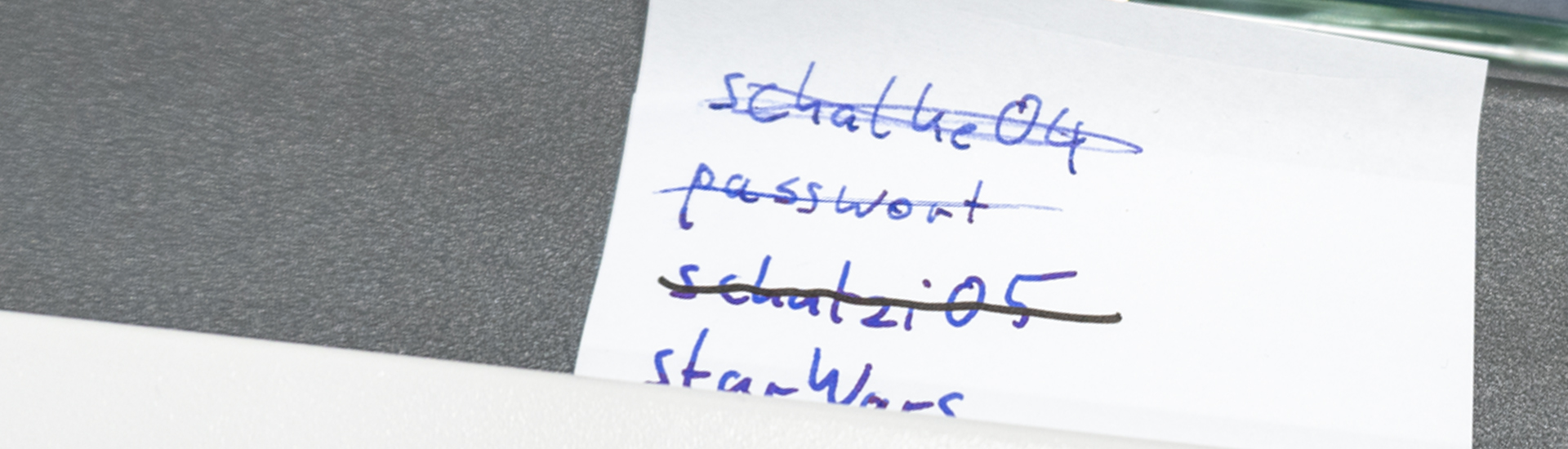

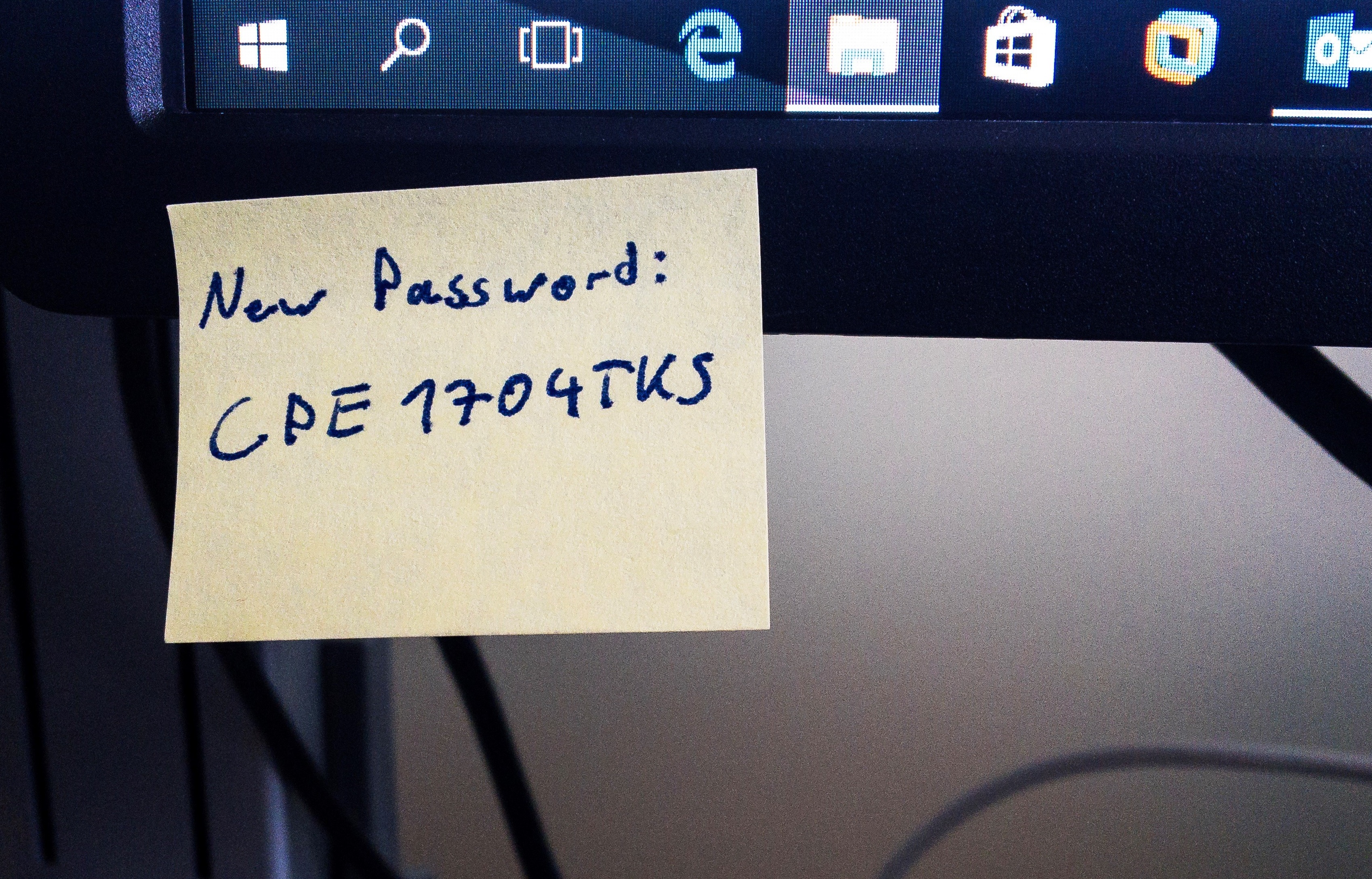

Putting it in black and white...

The Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) is now adopting this position in the current edition of its guidelines for basic IT protection. The somewhat cryptically numbered chapter “ORP.4.A8: Rules for password use” lists all the rules that apply to the handling of passwords. What is particularly interesting here is what is no longer in the rules - namely, that passwords must be changed at regular intervals. On the contrary, it explicitly states that: “A password MUST be changed if it has - or if there is suspicion that it has - become known to unauthorised persons.”

Specifically, this means that nobody should change their passwords any more - unless someone else knows them as well.

Convenience and a change of mind

People like to make things as easy as possible for themselves. And complex, long passwords are a thorn in the side of many users. So administrators around the world have come up with other ways to prevent passwords being reused, while increasing their security. For example, millions of users are tearing their hair out over draconian password policies that require at least one digit and two special characters or that prohibit the use of any of the last twenty passwords.

Nobody really wants to remember passwords that long and complex - let alone come up with a new one every few weeks. It is therefore common practice to enter iterations of a password, for example, “MyPassword”, directly followed by “MyPassword2”, then by “MyPassword3” and so on. Passwords that are very easy to guess are still widely used and yet have long been an absolute no-go for good reason - including perennial favourites such as “letmein” or “qwerty1234” - or even “liverpool1892”. Passwords like these are the first things criminals try when attempting to break into online accounts and user accounts in company networks. And they routinely keep appearing in lists with titles like “The 10 worst passwords”. To make matters worse, many Internet users still use the same password for several different things at once. In the worst case, a criminal not only gains access to a mailbox, but also straight to online banking or social media accounts.

If there is one thing a computer is good at, it is simply trying hundreds of thousands of different passwords blindly. Even input patterns that do not appear in any conventional dictionary, but are easy to type on a keyboard, such as “1q2w3e4r5t” or “qwerasdf1234”, are included.

There are whole lists of words with these standard passwords, such as the “Rockyou” list. Anyone can download this list, for free and completely legally. For example, companies can create blacklists of passwords that are not permitted for use in the corporate network.

But the fact remains - a password must still be long enough to make it difficult to crack. Only the length can make a password so secure that a disproportionately large amount of effort is required - the time it takes to crack a password increases exponentially with every additional digit, letter or special character.

Alternatives and extensions

What provides even more security is so-called multi-factor authentication. Instead of relying solely on a knowledge-based login factor - such as a password - it helps to add a second factor. This way, even the loss of the password is not a real problem, since a hypothetical attacker still needs the second login factor. This can be a special security token, a biometric feature or a one-time password from a special app.

Also on the way are FIDO2 tokens, which might even completely replace passwords. However, these are not yet very widespread and are not supported everywhere. Password managers are also a useful extension - the range of paid and free solutions is quite broad, so there should be something for everyone.

Regular checking

Data leaks occur all the time, and every time a large number of users are affected. Those affected only find out whether their own password has become criminals’ prey when it’s too late, their eBay account has suddenly been taken over and invoices for goods they have not ordered come flooding in.

Identity Leak Checkers from the Hasso Plattner Institute can be used by anyone who enters their email address to determine whether data associated with this address has been affected by major data leaks. If so, either change the password immediately, if this has not already been done - and if necessary delete or deactivate the affected account.